Other common names

Table of content

- Other common names

- age [float]

-

ageis typically expressed in years. However, we don’t recommend flooring “age” to get integer values, as flooring implies losing data. It is better to leave variables as floats (when they are floats) and let the analyst decide whether or not flooring this variable is necessary for their specific purpose. - accuracy [float]

-

accuracyrefers to a measure of performance; in many tasks, it reflects the percentage (0-100%) or fraction (0-1) of correct responses. We will always useaccuracyto refer to a performance measure that is a float and bounded in the [0-1] range. - correct [boolean]

-

correctis a boolean variable which indicates for a given trial or response whether it was correct or not. When no response was given when it should (i.e., timeout), correct evaluates toFALSErather thanNA. This is to avoid the case where people would be given a high performance score when in fact they avoided all difficult trials and responded correctly only to easy trials. - response_time [float]

- the meaning of

response_time(and its units) is not consistent across studies. For us,response_timeis the duration between the moment the participant fully completed their response on a given trial and the moment that the earliest possible correct response could have been completed by an AI agent with perfect knowledge of the task and ability to instantaneously execute the response. - Default unit: seconds

Other measures of durations exist and may be useful to describe a person’s response. If such additional measures are needed, they should be specified explicitly. For example

response_onsetresponse_offsetresponse_duration

Units for response times are not consistent across papers and publicly available datasets and one can find them expressed in either seconds or milliseconds. We decided to use seconds as the default unit for response times because:

- avoid “exception” by always using seconds as duration measure.

- avoid computation by keeping the units as they currently are in our raw data and task specs.

- avoid the temptation to round rt to integers when expressed in milliseconds.

- take advantage of the fact that most packages to analyse rt seem to be using seconds as a default unit; be congruent with what seems to be the default unit in fMRI measurements.

It is tempting to abbreviate

response_timeasrt; however, there are several other variables prefixedresponse_which do not have abbreviations. Spelling the names out, while making the name longer, makes the overall data structure more consistent and explicit.

- timed_out [boolean]

- indicates whether the participant failed to respond within the allocated time period.

- gender/sex [enum]

- gender and sex are not exactly the same. Sex refers to a biological sex while gender is a more complex construct. A person may have a male biological sex but identify as a women for example. Depending on the question asked, the variable should therefore be either

sexorgender. “What sex were you assigned at birth, such as on an original birth certificate?” is clearly a question about biological sex and should be coded assex. - The values for

sexshould be an enum:FemaleMaleOtherPrefer not to say

Units in variable names

According to [NASA 1999] Arthur Stephenson, chairman of the Mars Climate Orbiter Mission Failure Investigation Board:

“The ‘root cause’ of the loss of the spacecraft was the failed translation of English units into metric units in a segment of ground-based, navigation-related mission software, …”

from https://people.csail.mit.edu/jaffer/MIXF/CMIXF-12

Some variables have measurement units. Variables should use the standard measurement unit for their type (e.g., durations in seconds; defined below), or the default unit assigned to them specifically within this document. Variables that use a non-standard, non-default measurement unit MUST specify the units explicitly using the format <variable>_in_<unit>.

Examples:

-

age(by default in years) age_in_months

When the units are a single word it’s OK to use the complete word; if it has multiple words, it’s better to abbreviate them unless the abbreviation can lead to confusion or ambiguity. For example, prefer seconds to s but mpg to miles_per_gallon.

There are default units, these are marked with

*. In addition there are default units for specific variables. If a “standard” variable has a default unit, that default unit overrides the default in this list. For example, the default for duration is seconds.ageis a duration but its default is years rather than seconds.

This document does not cover the subject of units exhaustively and will be updated as new use cases arise. When in doubt, consult BIDS: https://bids-specification.readthedocs.io/en/latest/99-appendices/05-units.html https://bids-specification.readthedocs.io/en/latest/02-common-principles.html#units

The formatting of the units should probably be specified further, maybe using an international standard (https://ucum.org/ucum.html or the one Morty mentioned once in his presentation ?)

Standard variable name suffixes

Standard feature names

Variables may describe a feature or property of an entity, using the format

- length

- refers to the length in cm of a physical object. When possible use a more specific word (e.g., height, width, distance). Don’t use length to mean count or size!

- height, width

- refers to the height and width in cm of a physical object.

- weight

- refers to the weight in kg a physical object.

size- don’t use “size” as this term is ambiguous. “size” could refer to 180cm, “Medium” or 230x230. Instead, use a more specific term.

- count

- refers to the cardinality of the entity. If an observation/row has

car_count = 5this means that this particular observation involves a total count of 5 cars; this 5 is unrelated to other rows in the table.

Standard suffixes

All names below are not to be used alone but rather as suffixes (e.g., “block_type”, “stimulus_description”).

- *_type [enum]

- is always an enum. The meaning of the particular enum needs to be explained in a codebook. It can be tempting to use synonyms of “type”, in particular when “type” is already taken; such synonyms include things like “category”, “kind” or “set”. When those synonyms are not required (e.g., domain language) they should be avoided and replaced by “type”. Not all enums however need to be suffixed with “type”.

- *_description [string]

- is always a text (String) for human consumption. While it is not strictly necessary, a textual description can greatly facilitate the understanding and processing of the data by humans.

Standard aggregation suffixes

We will use the following names as suffixes to refer to particular operations in variable names. For example the mean of a variable “age” would be called “age_mean” (and not for example age_avg or age_m). We typically use the same name as the aggregation function name in R or Python. More specialized terms require explicit descriptions.

- mean

- average of the variable. Don’t use

avgoraverage. - median

- median of the variable. Don’t use

med. - mode

- mode of a variable.

- min, max

- minimum and maximum of a variable

- sd

- standard deviation of a variable. there are many other abbreviations for the standard deviations for the standard deviation but https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Standard_deviation uses SD and SD is the most common according to https://www.abbreviations.com/abbreviation/Standard+Deviation. However we won’t use sd in all caps.

- var

- variance of a variable.

- sum

- the sum on a variable (e.g.,

item_price_sum = sum(item_price)). Don’t use total to designate the result of a sum operation. - count

- integer value, refers to the count of a particular entity (e.g., a variable named

page_countindicates the number of pages). Note that “count” is different from “sum” (e.g., one can sum negative float values while count involves positive integers only) and from “index” (e.g., “this is the second” versus “there are two”). Note also that while the use “n” to refer to counts is much shorter and might be standard in some circles, “count” is more explicit and less error prone than “n” which may mean different things in other contexts (e.g., the length of the variable, an iterator). - quantile25, quantile50

- quantiles are similar to percentiles; both refer to the value of a variable x that splits the data such that a given fraction of the data is smaller than x. Quantile expresses that fraction as a number between 0 and 1 while percentiles express it as a percentage (between 0 and 100).

We use quantiles rather than percentiles because they allow us to name the resulting variables in a simpler way. We use the following convention:

quantile(x, q = 0.23)->quantile23quantile(x, q = 0.145)->quantile145

There could be an ambiguity when using quantile(x, q = 0.100) versus quantile(x, q = 1). However, note that quantile(x, q = 1) is in fact equivalent to max(x); quantile(x, q = 1) is median(x) and quantile(x, q = 0) is min(x). In these cases it is preferable to use the more direct name (max(x) rather than the quantile(x, q = 1)).

Standard transformation suffixes

In general, use the function name that was used to do the transformation. For example the log of a variable age would be called age_log (and not for example log_age or age_in_log). We typically use the same name as the transformation function name in R or Python. We will use the following names to refer to particular operations in variable names.

- log, log10, log2

- natural log, log of base 10, log of base 2. Always specify the base when using the log except for the natural log (this seems standard in R and Python).

- sqrt

- square root of a variable.

- pow2, pow3, pow4, …

- square or raised to the power of 3, 4, etc.

- floor, ceil, round

- flooring, ceiling or rounding a variable. Rounding may require specifying additional parameters.

- rank

- variables can be ranked (for example from the smallest to the largest values) and some values can be tied (in which case the rank will no longer be all integers). It might not be clear if the ranks are descending or ascending (e.g.,

age_rank). If such confusion arises it might be preferable to use a more direct name (e.g.,youngest_to_oldestoryoungest_first_rank).

Standard referencing postfix terms

Several variables are used to filter, identify or locate particular rows in a table or across multiple tables. Below, we list and clarify the ones we use and how we use them.

Note: some people start counting from 1 others from 0; here we follow the convention of always starting counting/indexing from 1.

- *_id [string, integer]

- if a column name is postfix with

_id(e.g.,participant_id,task_id) it is expected that there exists a table which has the same name (i.e., “participant”, “task), with a primary key namedidsuch that a value of in the first (particiapant_id = 215) refers to an entry in the second (a row in the participant table whereid = 215). It is expected that the values in a variable postfixed_idare unique within a “local scope” (e.g., a dataset); however, it is not expected that they are unique globally—for such purposes one should use the_uuid. - If there is a column named

id(i.e., without prefix) it is expected that there are other data tables or files that refer to this column; if such a link does not exist, useindexinstead. Finally, the postfix_iddoes not imply a particular value format: both integers and strings are valid formats. - *_name [string]

- Sometimes “name” is used in a way that is similar to id (e.g.,

study_nameortask_name). The difference between_idand_nameis that_nameis expected to be a readable string (e.g.,n-backversus “f346-r23v”). As with_id, it is expected that name refers to other data tables and that names are unique within a certain context (contrary to*_label). - *_uuid [ISO/IEC 11578:1996; string]

- Universally Unique Identifier (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Universally_unique_identifier) is a 128-bit number that can be generated on the fly and will most likely be unique. uuid can be used to assign a row a unique id without having to ensure that that number is not yet used by some other table.

- _uuid are expected to be unique (globally);

- _uuid are not expected to be human readable;

-

Example:

123e4567-e89b-12d3-a456-426614174000

There also exists a uid which we don’t cover here.

- *_hash

- sometimes it is useful to create a key by combining other keys. A hash is not strictly necessary as it can be recreated using other variables but it can be convenient for data processing. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hash_function

- There is not a single standard for hashing; rather there are multiple algorithms that can be used. We use both CRC32 (32 hexadecimal characters; e.g., “098f6bcd4621d373cade4e832627b4f6”) and SHA256 (base64 characters, e.g., “d14a028c2a3a2bc9476102bb288234c415a2b01f828ea62ac5b3e42f”); depending on the probability of collision (i.e., two hashes being identical); when that probability is deemed high, we use SHA256.

- *_index [integer]

- index should be favored when a variable is used for referencing and when order is important (often, but not always the chronological order). For example, “stimulus_position_index” implies its value points to an entry in a list of possible stimulus_positions. Note that “index” typically implies a context within which the indexing occurs and that context must be made explicit. For example, trial_index may index trials within a block or a timeline.

- *_repetition

- is used to count the number of times the same “thing” occurred (e.g., a participant completes the same test twice, the same stimulus appears multiple times). As with index, repetition assumes a context which must be clarified when ambiguous.

Repetition starts “counting” at 0 rather than 1; *_iteration instead of *_repetition would solve this issue but is less explicit and thus less preferred.

- *_label [string]

- an text attached to a variable; expected to be human readable, but not unique.

We avoid the use of

*_numberbecause it is typically too general and thus confusing.

Indexing contexts

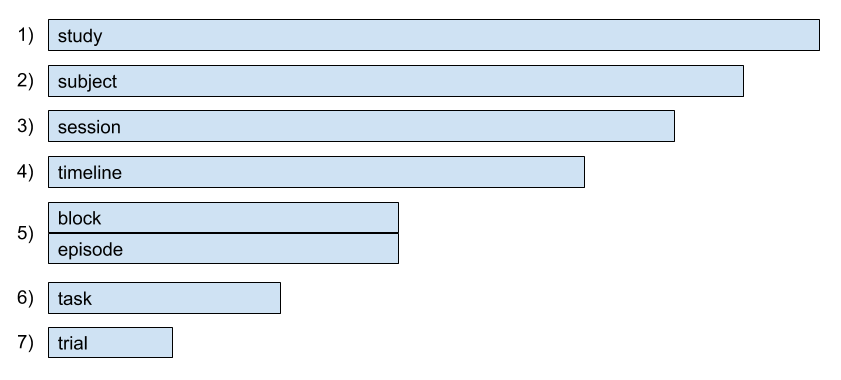

We use several variables to index particular types of entities. As stated earlier, a context for indexing must be specified. We use the convention illustrated in the figure below:

The figure above indicates that the largest context is study. subjects of a study are indexed within a study; the first subject has index 1, the second has index 2, etc.

A subject may complete multiple sessions. Within a subject, the first session has index 1 and the second session has index 2, etc.

Timelines are indexed within sessions and subjects. The first timeline in the second session of the third subject has timeline_index = 1.

Blocks are indexed within a timeline. The third block, in the first timeline of the fourth session of the sixth subject has block_index = 3.

Episodes are also indexed within a timeline. This means that the first episode within each timeline has episode_index = 1 and this index continuously increases over the course of a timeline.

Tasks are indexed within blocks; if a block involves multiple tasks, each task will have its own index value. Trials are indexed within tasks; if a block alternates between two types of tasks (i.e., task_index = [1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, …], the trial indices might look something like [1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 4, 4, …].

Formats

Numeric values

It can be sometimes tempting to floor, ceil or round a float variable into an integer. For example, one might assume that age when expressed in years should be an integer or that response times when expressed in milliseconds should be integers as well.

Such data transformations should be avoided as a default because they lose data. A data analyst who wishes to round a variable for a particular purpose can still perform that operation later one and name her variables accordingly (e.g., age_floor).

Date, date time and timezones Variables that express a “datetime” must be formatted using ISO 8601 express time at a resolution of the millisecond or smaller include a timezone if possible express participants local date and time in day

Imagine an online study with participants all over the world. At 6pm UTC, it is 11am in Los Angeles, 2pm in New York, 8pm in Paris and 3am (of the next day) in Tokyo. One would clearly expect a cognitive test completed at 6pm UTC to yield very different results depending on participants’ local timezone (e.g., 11am versus 3am). From a psychological point of view then, is participants’ local time (for a system administrator, on the other hand, UTC time would be more useful). Hence, we should express datetime variables in participants’ local timezone.

There are cases where recording local timezones may infringe privacy. In such cases there are several possible solutions: remove timezones (11am Los Angeles -> 11am, 2pm New York -> 2pm) replace timezones while keeping date and time in day (11am Los Angeles -> 11am UTC, 2pm New York -> 2pm UTC) keep timezones but shift days (cf BIDS) remove timezones and shift days

We recommend solution 1, where timezones are “missing”, rather than the other solutions which inject “lies” in the data. Hence, when timezones are not specified we assume (contrary to BIDS) that date_times are expressed in participants’ local (but unknown) timezone.

Example: “2009-10-31T01:48:52.512Z” Note: the “year-month-day-hour-minute-second-ms” ordering is consistent with the hierarchy principle and provides a better view of the raw data than the format that would display day-month-year. Note: we diverge here from BIDS because BIDS accepts missing timezones (assuming it implies the local time of the data viewer) and does not require millisecond precision (but does require format consistency within a dataset; https://bids-specification.readthedocs.io/en/latest/02-common-principles.html#units).

Languages

When referring to particular languages, we use the ISO_639-1 standard.

Colors

Colors can be expressed in many different ways,including hex (e.g., #A9A9A9), RGB (e.g., (169, 169, 169)) or CMYK (e.g., (0,0,0, 33.73). We use two conventions to describe colors depending on the use case.

If the exact color value is not relevant and the information is destined for human readers, we refer to colors using color words (e.g., “red”, “green”, “blue”).

If, however, colors need to be specified exactly, we use the RGBA format which defines a color using 4 floating point values, each within the [0-1] range, and where the the first three number define the red, green and blue components of the color and the last number it’s opacity (0 = transparent, 1 = opaque).

Format of data values

Sometimes it is necessary to spread a table by one of its variables; meaning that the values of a particular variable become the names of new columns. In order for those new columns to be named in a way that is consistent with this style guide it is necessary that variable values (in particular for enums) follow the same standard as the variable names: they should be in lower_snake_case.

Missing values and errors

There is considerable variability in what is considered a missing value and how to deal with them. For example, in a go/no-go task where the correct response to no-go stimuli is to NOT respond, should a non-response be considered a missing value? Can a missing value evaluate to a correct response on a trial? In a different test, if a person had to choose between two options within a certain time interval and failed to respond within that time, should the accuracy of the trial be set to NA as the person did not in fact make a choice between the two options?

First of all, it is useful to have a variable that explicitly indicates whether the participant timed out or not (rather than having to infer this information by looking at the presence of missing values within a particular task context).

Second, missing values should be applied only to the data that is in fact missing. If a person did not press a key in the go/no-go task, the response time would be missing but that would be considered reflecting the participant’s choice for a “no-go” and in a particular trial that response would evaluate to correct.

Third, a response evaluates to correct if a specific set of conditions are met and evaluates to incorrect in all other cases. For example, in the “two choice” task with limited time to decide, a correct response would be defined by choosing the better option within that time limit. If no response was given (i.e., missing value) that condition is not fulfilled and thus the response evaluates to incorrect (and not NA). This is an important point because some people might instead decide to evaluate only those trials on which the person actually made a choice. Evaluating accuracy conditional on there being an input or not might be valid in some contexts but will typically lead to very different results. Imagine for example a case of a test where the questions asked are easy or hard. A weak student that answers correctly only the easy questions should not get a higher score than a better student who responded to all questions and made some errors on the hard questions.

Regarding the coding of missing values, some people also use various numeric codes to “tag” missing values (e.g., -9 or -99). This can lead to errors down the line (e.g., missing values are not noticed or missing and actual values look similar). This practice should be avoided and missing values should be coded explicitly as NA.

Default units

Below we list the names we use for different measurement units by measurement dimension (e.g., duration); these are the names that should be used when suffixing variables (to explicitly indicate units; e.g., response_time_in_milliseconds). Default units for each measurement dimension are marked by an *, those units need not be explicit in the variable names. Note that some specific variables listed in this document have their own default units (e.g., age in years); the variable specific default unit override the dimension default (i.e., duration is typically expressed in second, but for age we use years).

Duration

- milliseconds

- *seconds

- minutes

- hours

- days

- months

- years

- decades

- centuries

Weight

- mg: milligrams

- g: grams

- *kg: kilograms

- pounds

Length

- mm: millimeters

- *cm: centimeters

- m: meters

- km: kilometers

- inches

- feet

- feet_inch: mix of feet and inches (e.g., 5”3’)

- pixels: number of pixels; the pixel size in cm depends on subjects screen size and resolution.

- screen_fraction: fraction of subject’s screen diagonal expressed between 0 and 1, from bottom-left to top-right. For example, if the diagonal of the screen is 40cm long, a screen_fraction of 0.25 corresponds to 10cm.

For more information on viewports, see: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/CSS/length#Viewport-percentage_lengths

Frequency

- *hertz: count per second